"When I Write, I Bleed."

"There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed." —Ernest Hemingway

“Happiness in intelligent people is the rarest thing I know.”

— Ernest Hemingway

The passage of time has led many to falsely romanticize the, historically, greatest of the great: the most genius composers, painters, writers, etc., are all1 believed to be, from someone who hasn’t studied them thoroughly, as generally mentally stable: they were knocked down by the establishment yet they eventually rose to spectacular success and lived ‘happily ever after.’

(At very least I often catch myself subconciously thinking this, but I don’t necessarily know how wide-spread the notion is.)

The general populace (i.e. non-Substack-ers and/or non-nerds/weirdos/dorks, etc., lol) has heard stories of the greats occasionally falling from grace but the widespread consensus is not that those like Rembrandt and, as quoted, Hemingway were perfect but that they were far elevated in their mental state and far more stable than the average person—which supposedly allowed them to produce their masterpieces.

In reality, though, the ones who are the most admired and acclaimed are more often than not the antithesis of what society considers an admirable person.

Bipolar mood swings, severe bouts of depression, alcoholism, manic episodes, hallucinations, violent tempers, narcissism, and addiction to hard drugs are all found commonly in the private lives of the most recognizable faces of history, but these traits would be considered, at best, problematic by the lens of society.

(Below is a list of such people.)

1. Sylvia Plath - Poet

Author of the infamously dark, The Bell Jar, Plath struggled with depression throughout all of her life and found it very difficult to express her feelings of despair in ordinary ways, which led her to citing her writing as the only way to show others “what it is like to be alive in this body-mind.” With this, themes of suicide were omnipresent in both her life and work. Plath tried multiple times to kill herself and, as some critics theorize, the aforementioned, The Bell Jar, is directly inspired by a visit to a psychiatric ward following one of her unsuccessful attempts.

The final years of her life were tumultuous at best: after a miscarriage, her marriage spiraled and, ultimately, her husband divorced for someone she thought was better. This left Plath feeling at an all-time low, especially considering she was the lone adult in charge of her two kids. The catalyst for her death, though, was that Plath was deeply aware that The Bell Jar was receiving almost zero critical attention from the writing community at the time and this upset her so terribly that, at the age of thirty, she was found dead after intentionally inhaling gas from her oven in 1963.

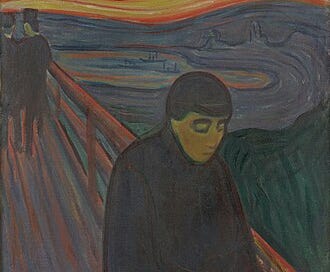

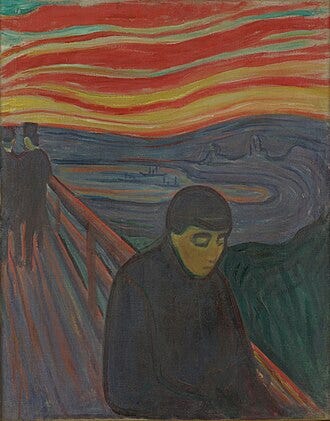

2. Edvard Munch - Painter

“From the moment of my birth, the angels of anxiety, worry, and death stood at my side, followed me out when I played, followed me in the sun of springtime and in the glories of summer. They stood at my side in the evening when I closed my eyes, and intimidated me with death, hell, and eternal damnation. And I would often wake up at night and stare widely into the room: Am I in hell?”

—Edvard Munch

This worry Munch describes likely stemmed from his overly strict and religious father and the sudden death of his mother early in life. Munch often expressed fear of becoming insane: his sister was institutionalized and he feared he would be as well. He exhibited signs of borderline personality disorder (BPD), schizophrenia and chronic impulsivity, among others. All of these complex emotions Munch pent up culminated in his very distinct, yet very disturbing, style of painting with titles often based on emotions themselves (such as, Anxiety (1894) and Despair (1892)).

In the late 1890s, he found success in many of his paintings along with brief happiness, but alcoholism crept up on Munch and led him to spiral. He eventually recovered from addiction but from roughly the 1910s and onward, he led a life of general seclusion, suffering from horrible, chronic maladies which he would commonly depict in his work. He painted right until his death in 1944.

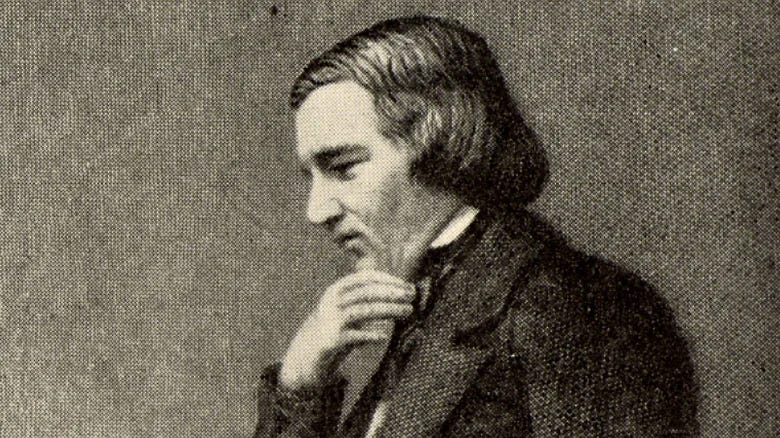

3. Robert Schumann - Composer

In what must’ve felt like back-to-back losses for Schumann, his sister and father died in the same stretch of ten months. In response, he began keeping a diary, which he maintained for the remainder of his life, to stop “painful hours from eating up the memories of happier times."

To combat depression from this period, Schumann started training professionally in piano, but his fingers quickly gave out before his career as a pianist could even begin. He tried everything to make the pain of when he moved his fingers more bearable so he was able to play piano, but, ultimately, he never recovered.

Then, his brother, Julius, died, and Schumann locked himself away from the rest of the world: shifting his focus to composing music, where he was determined to excel. Composing offered short respite for him, but while he was concerned with music, he, and his sister-in-law, Rosalie, both fell ill with malaria.2 After her death from the sickness, Schumann wrote of the night she died as "the most frightful of my life," he was likely frightened by his own mortality and, like Munch, soon became deeply afraid of going “mad.” During this time, he fell into a great bout of depression and attempted suicide unsuccessfully, but close after found himself as a legitimate composer despite, at points, working extremely unhappily.

The main tragedy of Schumann’s life then became, not his strange proximity with death at all-times, but his newly persistent auditory illusions. He recounted hearing an A-note constantly ringing his ears among other things. And, he knew these sounds weren’t real; his worst fears were confirmed: he was, in fact, going “mad.” This fact tortured Schumann and he, once again, unsuccessfully attempted suicide, forcing his wife (the famous Clara Schumann) to enter him into a mental asylum. There, his delusions only got worse and with newly experienced seizures, pneumonia took his soul away easily in 1856.

Schumann’s compositions reflected his mental state throughout much of his life: his music has the same air of tragedy, painful melancholy and deep rumination, yet sometimes terrible mood swings, as his countless diary entries do. His music truly strikes a poignant emotional chord in the listener. 3

After writing this list, I conclude that nearly every hyper-famous artist or visionary, prior the year 2000, were all either narcissistic, bipolar, drug addicted or depressed or some derivation of those characteristics—showing that you certainly don’t have to be a saint nor perfect for your work to touch the brains of so many.

This leads me to the conclusion that the best, most seen art is art that harnesses the artist’s own pain and suffering and puts their complex emotions on stage.

The linking characteristic between all of the people I’ve mentioned is that they bleed onto their canvas; they bleed onto their pages; they bleed onto their composition; they coated their media with a thick layer of rich, deep crimson blood and that is what made them the best and the admired.

“There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”

— Ernest Hemingway

Even though the torture artist stereotype is widely known it is often not realized to be as omnipresent it is throughout history.

Schumann eventually recovered from malaria.

While this list isn’t necessarily composed of house-hold names, those that are house-hold names still follow suit (Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Michelangelo). I simply picked the most interesting cases that I’ve found, and therefore the easiest to write on.